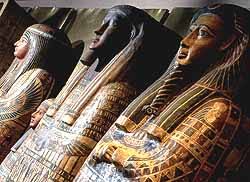

Coffin set belonging to the temple singer Tamutnofret, composed of an outer coffin, an inner coffin and a "mummy-cover", a full-length death mask that was placed over the mummy. The origin of the set is a now unknown grave in Thebes. It can be dated back to the reign of Ramses II (approx. 1279-1213 BCE). Painted and gilded wood. Louvre, Paris

Funerary reuse essentially involves the re appropriation of ideologically charged objects, and in the case of 20th and 21st Dynasty coffins, this reuse occurred in the context of economic and social crisis. A coffin was essentially meant to make a functional link between the thing and the person – to transform the dead into an eternal Osirian and solar version of him or herself. The coffin was believed to ritually activate the dead. Profoundly, during the 21st Dynasty (and probably during many other time periods), the Egyptians were able to DE-fetishize these objects. They were able to separate the coffin from the essence of one

dead body and modify it for another. It is difficult to understand how the ancient Egyptians were able to break the link between the person and this sacred thing. I suspect there were magical spells and rituals involved to keep the dead at peace before and after they were removed from the container, but the Egyptians did not leave any such information preserved for us. But the reuse was also economically driven. Access to high quality wood from the Lebanon or elsewhere was impossible, and people had to look elsewhere for this most basic coffin resource. Some Egyptologists may consider coffin reuse to be an immoral crime that happened rarely, but the ancient Egyptians may have considered the non-performance of ritual transformation for those who had just died to be an egregious cultural and social failure. Coffin reuse was a creative negotiation of this economic-social-religious crisis. In other words, it was not the reuse of a coffin that was aberrant; if anything was aberrant, it would have been refusing to provide the recently deceased with trans formative ritual activity by means of funerary materiality, just because there was no access to wood that had not been previously used.

The Egyptian elite was buried in a coffin placed inside another coffin -- in ensembles of up to eight coffins. This was intended to ensure the transformation of the deceased from human to deity

Boxes and other forms of containers are technologies that arise at given points of time in various cultures. Everybody knows the ancient Egyptian practice of mummifying their dead. What is perhaps less known is that they placed the mummies inside layer upon layer of coffins,"

Ancient Egyptian history encompasses a period of nearly three thousand years, up to the Roman conquest in the year 30 BCE. Today, museums all over the world possess mummies or coffins that have contained mummies of more or less prominent men and women.

The child king Tutankhamun (1334-24 BCE) was buried in as many as eight coffins,

"For men and women who were members of the ancient Egyptian elite at that time, three or four coffins were not unusual," "They also played a key role in the process that would link the deceased to their ancestors: to Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and to Amun-Ra, the sun- and creator god

The rituals and the myths that were reiterated during the seventy days that a funeral lasted are symbolically rendered on the coffins. The components of each nest, including the mummy-cover, the inner and outer coffins -- reflect the Egyptians' view of the world.

"The decorations, the forms and the choice of materials signify a unification of the two myths about Osiris and Amun-Ra respectively. On the outer coffin, the deceased is portrayed as Osiris, with a mummified body, a blue-striped wig and a pale, solemn face. The coffin is painted yellow and varnished, and must have shone like gold. The very richest Egyptians did in fact use gold leaf on their coffins."

"The choice of colour is not coincidental: it represents the light and its origin in the sun. That the figure of Osiris is being bathed in sunlight can, in my mind, only mean one thing. The decoration invokes a well known mythical image: when the sun god arrives in the throne hall of Osiris in the 6th hour of the night and the two deities join in mystical union. According to the Egyptians, this union was the source of all regeneration in nature, and it was here, at the centre of this 'catalyst of life' that the deceased wanted to be placed for all eternity."

the innermost layers of the coffin nests dating from the 19th dynasty (approximately 1292-1191 BCE) were fashioned as living humans in their best outfits. The innermost layer was the most important one, since it shows the objective of the afterlife transformation: the "state of paradise" to which these people aspired involved not only a mystical union with the gods; but more importantly a return to their old "self."

this custom served to distinguish the sacred from the more mundane surroundings.

The numerous layers of coffins around the mummy functioned as repeated images of the deceased, but also as protective capsules, similar to the larvae's pupa before its transformation to a butterfly. Such repeated imagery is a well-known theme in religious art and literature. In the Egyptian coffin sets, they symbolize the eternal, life-giving pendulum of the sun god between heaven and earth -- a process in which the ancient Egyptians hoped to participate in their afterlife."

Even though complete Egyptian coffin nests still can be found intact in some places, most have been disassembled and are today scattered in museums all over the world.

Funerary reuse essentially involves the re appropriation of ideologically charged objects, and in the case of 20th and 21st Dynasty coffins, this reuse occurred in the context of economic and social crisis. A coffin was essentially meant to make a functional link between the thing and the person – to transform the dead into an eternal Osirian and solar version of him or herself. The coffin was believed to ritually activate the dead. Profoundly, during the 21st Dynasty (and probably during many other time periods), the Egyptians were able to DE-fetishize these objects. They were able to separate the coffin from the essence of one

dead body and modify it for another. It is difficult to understand how the ancient Egyptians were able to break the link between the person and this sacred thing. I suspect there were magical spells and rituals involved to keep the dead at peace before and after they were removed from the container, but the Egyptians did not leave any such information preserved for us. But the reuse was also economically driven. Access to high quality wood from the Lebanon or elsewhere was impossible, and people had to look elsewhere for this most basic coffin resource. Some Egyptologists may consider coffin reuse to be an immoral crime that happened rarely, but the ancient Egyptians may have considered the non-performance of ritual transformation for those who had just died to be an egregious cultural and social failure. Coffin reuse was a creative negotiation of this economic-social-religious crisis. In other words, it was not the reuse of a coffin that was aberrant; if anything was aberrant, it would have been refusing to provide the recently deceased with trans formative ritual activity by means of funerary materiality, just because there was no access to wood that had not been previously used.

The Egyptian elite was buried in a coffin placed inside another coffin -- in ensembles of up to eight coffins. This was intended to ensure the transformation of the deceased from human to deity

Boxes and other forms of containers are technologies that arise at given points of time in various cultures. Everybody knows the ancient Egyptian practice of mummifying their dead. What is perhaps less known is that they placed the mummies inside layer upon layer of coffins,"

Ancient Egyptian history encompasses a period of nearly three thousand years, up to the Roman conquest in the year 30 BCE. Today, museums all over the world possess mummies or coffins that have contained mummies of more or less prominent men and women.

The child king Tutankhamun (1334-24 BCE) was buried in as many as eight coffins,

"For men and women who were members of the ancient Egyptian elite at that time, three or four coffins were not unusual," "They also played a key role in the process that would link the deceased to their ancestors: to Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and to Amun-Ra, the sun- and creator god

The rituals and the myths that were reiterated during the seventy days that a funeral lasted are symbolically rendered on the coffins. The components of each nest, including the mummy-cover, the inner and outer coffins -- reflect the Egyptians' view of the world.

"The decorations, the forms and the choice of materials signify a unification of the two myths about Osiris and Amun-Ra respectively. On the outer coffin, the deceased is portrayed as Osiris, with a mummified body, a blue-striped wig and a pale, solemn face. The coffin is painted yellow and varnished, and must have shone like gold. The very richest Egyptians did in fact use gold leaf on their coffins."

"The choice of colour is not coincidental: it represents the light and its origin in the sun. That the figure of Osiris is being bathed in sunlight can, in my mind, only mean one thing. The decoration invokes a well known mythical image: when the sun god arrives in the throne hall of Osiris in the 6th hour of the night and the two deities join in mystical union. According to the Egyptians, this union was the source of all regeneration in nature, and it was here, at the centre of this 'catalyst of life' that the deceased wanted to be placed for all eternity."

the innermost layers of the coffin nests dating from the 19th dynasty (approximately 1292-1191 BCE) were fashioned as living humans in their best outfits. The innermost layer was the most important one, since it shows the objective of the afterlife transformation: the "state of paradise" to which these people aspired involved not only a mystical union with the gods; but more importantly a return to their old "self."

this custom served to distinguish the sacred from the more mundane surroundings.

The numerous layers of coffins around the mummy functioned as repeated images of the deceased, but also as protective capsules, similar to the larvae's pupa before its transformation to a butterfly. Such repeated imagery is a well-known theme in religious art and literature. In the Egyptian coffin sets, they symbolize the eternal, life-giving pendulum of the sun god between heaven and earth -- a process in which the ancient Egyptians hoped to participate in their afterlife."

Even though complete Egyptian coffin nests still can be found intact in some places, most have been disassembled and are today scattered in museums all over the world.

Comments

Post a Comment