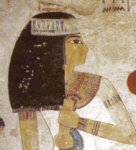

NAKHT AND HIS FAMILY

Nakht

, means

, means "strong", held the positions/titles of

"scribe"and

"serving priest". his wife, Tawy, was a chantress of Amon, and her son was called Amenemapet.

The title

"scribe"(which is usually placed second) simply means that he had received the education of an official, whilst his other, that of

"wenuti"is so rarely used (even in other tombs) that it must indicate a very secondary function. Within the texts of the walls (and the small statue) this word is written in five different ways (

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  ). In each case this was followed by the name

). In each case this was followed by the name "Amon", and which in each case has been removed. The title indicates a class of priest or temple official whose duties and rank are not very clear. Its use to identify an individual is very rare. It clearly refers to members of a roster whose period of service was fixed to certain hours of the night or day. It would appear that they were laymen, summoned to perform short duties of service in the temple and who thought of it as an honour to fulfil the simplest tasks, thus explaining why few officials carried the title except those who, like Nakht, had no other definite positions of office in administration. Thus the translation as

"serving priest"or probably more correctly

"priest of the hours"(of

"Amon") seems appropriate. The determinative

, found at the end of two versions of the word, used rarely in this tomb, is also associated with the word

, found at the end of two versions of the word, used rarely in this tomb, is also associated with the word "astronomer", and has given rise to the thought that Nakht may have been an

"astrologer"of the temple of Amon (although the word "temple" is never included in the texts.

His titles and name are usually followed by the hieroglyphs for

"true of voice", interpreted as

"justified"or

"deceased". This originates from the fact that the dead person must appear before Osiris and the scales of truth (the "weighing of the heart ceremony"), where his heart is weighed against the feather, the symbol of the goddess of truth, order and justice, Ma'at. If the heart equals the weight of the feather then the person is proved true and honest, i.e. justified, and can proceed into to afterlife. The scene of the "weighing of the heart" does not appear in this tomb.

Despite the small size of the tomb it can hardly one of a poor man or a person of no important position. To have the wherewithal in order to produce a tomb of this quality he certainly had something, perhaps he had close connections with the royal court or the royal family itself, although there is no indication of this in the tomb decoration. Regarding the period in which he lived, there can be not doubt, the erasure of the name of Amon from the texts in the complex shows that it was at least prior to the Akhenaton era. the relationship of the decorative style indicates that he must have lived during the reign of Thutmosis IV and Amenhotep III.

Tawy

, is identified most commonly in the tomb as

, is identified most commonly in the tomb as "his beloved, the chantress of Amon". Her identity only appears five times, and her name only four times, each time the deletion of the name "Amon" has also removed other characters.

- On the north wall, upper register, she is

"His sister, his beloved, the chantress of [Amon], Tawy.". On the lower register, the columns above the couple have been left without text.

- On the south wall, she is only mentioned in the badly damage area of the false door (centre top), where all that remains for certain is

"mistress of the house".

- On the east wall - left-hand side, there is only room for

"His sister, the chantress of [Amon], Tawy, justified.". However, only the last two characters of

"His sister"and

"justified"have survived the removal of the name "Amon".

- On the east wall - right-hand side, she is named once:

"His sister, his beloved, with a place in his heart, the chantress of [Amon, Tawy], justified."Here her actual name has been lost by the removal of "Amon".

- On the west wall - right-hand side, she is mentioned twice in the upper register on the left-hand side. Firstly in the blue text, as:

"His sister, the chantress of [Amon], mistress of the house, Tawy."Then, in multi-colour, as:

"His sister, his beloved, with a place in his heart, [the chantress of Amon], Tawy."

- On the west wall - left-hand side, no text to identify her has survived, the only text is that which states that the son is hers.

Note that she is only referred to as "justified" twice. Also, again only twice, is she referred to as

"mistress of the house", which actually identifies her as "his wife"; the term "sister" being used for both "wife" and "sister".

Tawy held the title as

"chantress of Amon", like most women with any resemblance of rank, thus it is uncertain that the title entailed anything other than being possibly associated with the temple of Amon, just as her husband was.

Children

, who is not described explicitly as Nakht's son, appears on the rear wall - left side, in the bottom register of the scene of "Beautiful Festival of the Valley". He is actually identified as

, who is not described explicitly as Nakht's son, appears on the rear wall - left side, in the bottom register of the scene of "Beautiful Festival of the Valley". He is actually identified as "her son"and may have been from a previous marriage of Tawy. In the one and only occurrence of his name, as elsewhere, the hieroglyphs spelling the name "Amen" (often used in names for "Amon", although the hieroglyphic spelling is the same) has been removed.

Other sons and daughters doubtless appear in the tomb, but were never specifically inscribed as being such or even named.

Comments

Post a Comment