The Ministry of Antiquities has completed the reconstruction and conservation of El-Wardian tombs no. G990 and no. G989 in Kom El-Shoqafa site in Alexandria. Both tombs were on display in the garden of the Greco-Roman Museum but were dismantled and transferred in 2009 to the Kom El-Shoqafa archaeological site within the project of development and restoration of the museum.

the works were carried out according to scientific methods and using non-invasive materials during the reconstruction.

the reconstruction work of tomb no. G989 began in November 2017 and completed in 2018, while fine restoration work started immediately. A special entrance was then created to facilitate its visiting.

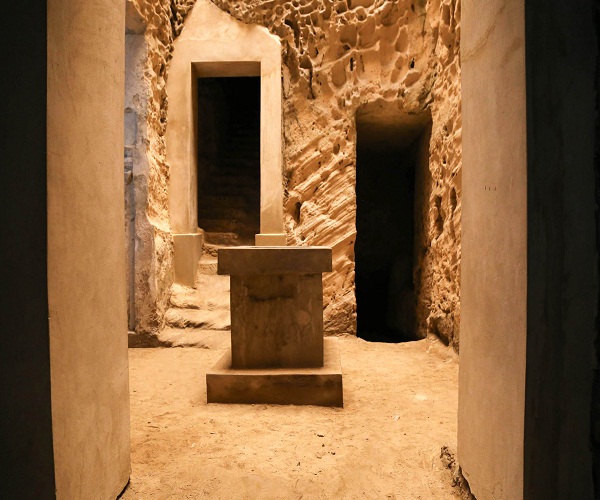

The reconstruction and restoration work in tomb No. G990 began in February 2019 it is now almost completed except the ceiling and the tomb’s front pillars.

the two tombs were part of the Alexandria western cemetery which was known as “the city of the dead”.

Both tombs were discovered by Evaristo Breccia in the Al Wardian site in the first decade of the 20th century, where they were carved in the rock and there walls are decorated with paintings.

In 1952 both tombs were transferred to the Graeco-Roman Museum. Tomb no G990 dates to the Ptolemaic era and consists of a burial chamber with vaulted ceiling showing remains of colours. Its walls are decorated with geometric signs and it has a sarcophagus with headrest.

Tomb no G989 dates back to the Roman Period and its burial chamber has two supporting columns with pillar crown and a semi-circle ceiling.

Comments

Post a Comment